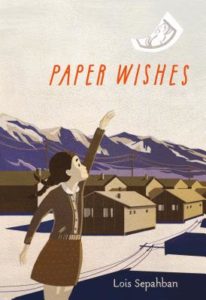

We are delighted to have Lois Sepahban, author of Paper Wishes, stop by to answer some of our questions. (See our craft review here.) Below you’ll find Lois’s thoughtful responses, which give insight into her writing process and research process, as well as the story itself. Lois hails from Minnesota and has written non-fiction for children. Paper Wishes is her first novel.

We are delighted to have Lois Sepahban, author of Paper Wishes, stop by to answer some of our questions. (See our craft review here.) Below you’ll find Lois’s thoughtful responses, which give insight into her writing process and research process, as well as the story itself. Lois hails from Minnesota and has written non-fiction for children. Paper Wishes is her first novel.

KidLit Craft: What gave you the idea for the story? What elements of the story do you have strong personal connections with?

Lois Sepahban: I grew up in central California, not far from Manzanar. One might think that because of this, I learned all about the history of Manzanar—through field trips and guest speakers to classrooms and such. But I did not. Manzanar was given just a few sentences in my history textbooks if it was mentioned at all. This purposeful ignoring stoked my curiosity. I read every nonfiction book I could find about Manzanar and the other World War II prison camps. In one of these books, I saw photographs of children imprisoned there and a story began to take shape in my mind.

Because I grew up in the area, I was familiar with the climate—the dust, the dry, cracked earth, the difficult task of keeping a garden alive. It was easy to incorporate these setting details into the story.

What was your research process? How did you decide what details to include and what to leave out?

When I become interested in an idea, I do random research here and there. I may check out a book at the library one week. A month later, I might watch a documentary. At some point, I talk to someone who has lived a similar story. All of this preliminary research helps me to figure out what story I want to tell.

When I was writing Paper Wishes, this period included watching interviews of survivors of the World War II prison camps on densho.org and revisiting Manzanar.

During this time, I have an epiphany of sorts—something I read or hear gives me goosebumps and I know what my story will be. With Paper Wishes, that moment occurred when I read a newspaper article in which a man who had been a prisoner at Manzanar said that at some point, dogs just started showing up at the camp.

After this, I do intentional research. For Paper Wishes, that included setting details (old maps and photographs were helpful since most of the camp was torn down after the war), historical timelines, political documents (like Executive Order 9066), and more survivor interviews.

Once I feel like my brain is saturated with information, I put my research aside and write. After drafting, I look back at my research to make sure I’ve gotten the details correct. And in the case of Paper Wishes, my editor arranged to have a historian at Manzanar read the galley and provide feedback.

As for which details to include and which to leave out, I let that happen as naturally as possible through the telling of the story. Because I’m not referring back to my notes as I draft, the historical details that end up being included are the ones necessary to the telling of the story. Later, I might find that I need to include details that were left out during drafting.

Can you talk about the role of silence in Paper Wishes? Was it always your plan for Manami to be non-verbal for most of the book, or did that develop along the way? How did her inability to use language challenge you in terms of depicting her relationships and her communication style?

I didn’t intend for Manami to stop speaking when I began the story. You can imagine that after writing the scene where her dog is taken from her, I needed to take a break. I went for a walk, and when I returned and sat down to write again, I discovered that Manami had stopped speaking.

For me, there was a lovely ignorance in writing a first novel. I had no audience in mind except myself and my critique partners. I didn’t worry at all about how I would tell a story with a main character who didn’t speak. I am an introspective person and so much of my life happens inside of my mind—conversations continue long after my partner has left the room, for example, and I pay more attention to what people say without words than what they say with them. So it wasn’t difficult to write about Manami in this way. But I knew that Manami would require people who loved her and supported her in order to survive her trauma. This story, then, isn’t just a tribute to Manami’s strength, but also a tribute to the depth of love her family and friends felt for her. Kimmi, in particular, a child herself, intuitively understands what Manami needs from her, and she is willing to give it. She doesn’t walk away from Manami, which may have been easier for her. She stays in that place of heartbreak with her friend, loving her and supporting her, confident that her friend will make it to the other side of her grief.

You incorporate a number of different responses to the “prison-village”–Kimmi’s optimism; the wild boy’s resistance; the workers’ compliance but secret work against the soldiers; the parents’ acceptance/not talking about it; Ron’s work to make things better–to care for the people around him. How did you find/discover these different characters and choose which to include?

I mentioned densho.org before, and I’ll repeat it here. There are thousands of interviews there, most of survivors, but some of non-prisoners who had lived and worked at the camps. I’m pretty sure I watched and/or read all of them. So many people. So many perspectives.

Lois Sepahban, author of Paper Wishes (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2016)

Similarly, the family is full–three generations–but spare–only one grandparent, siblings away at the opening. So it feels like a substantial family, but sparse enough to handle in the space allotted. What were your conscious choices in trimming the family tree?

When I began writing in earnest, I was a third grade teacher. I loved reading historical fiction with my students, but for this age reader, the offerings are few. I wanted Paper Wishes to be read by third grade children, and I knew that I had to limit characters to make the story as streamlined as possible.

At any point did you get pushback on Yujiin not returning at the end?

Honestly, pushback only came from myself. I really wanted Manami and Yujiiin to be reunited at the end of the book. I imagined Yujiin escaping from the crate and running after the bus. I imagined him following the train tracks from Seattle to California. I imagined him knowing right where to turn off for the road to Manzanar. I pictured him running through the gate, through the camp, into Manami’s arms. But that wasn’t realistic. And the truth is that the loss of Yujiin is a symbol of all Manami and her family lost that could never be recovered. To return him to Manami at the end would be like saying, see, it wasn’t so bad after all.

What can fans of Paper Wishes look forward to?

Next up from me is more middle grade historical fiction. I love middle grade, so I will certainly keep writing middle grade novels, and I may even try my hand at contemporary stories.

Thanks, Lois!

After years of reading long Victorian novels, Becky Levine worked in closed-captioning, where they basically paid her to get rid of words. Somehow, that early mash-up of story and editing led to the picture-books she writes today. Becky is the author of two books for Capstone Press and is a member of SCBWI. She lives in California’s Santa Cruz mountains and works as Grants Manager for a regional nonprofit. In her free time, Becky travels with her husband in their Vanagon, including frequent road-trips to visit their son, and knits very simple baby blankets.

COMMENTs:

0