craft review by Kristi Wright

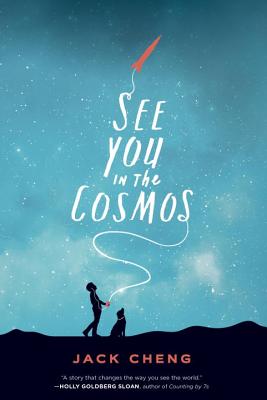

In See You in the Cosmos, author Jack Cheng introduces us to the protagonist, Alex Petroski, who is in the middle of creating a Golden iPod that he is determined to rocket into space to teach aliens about humanity. From beginning to end, the novel is a transcript of the Golden iPod’s audio. Through this unique narrative device, we readers become the aliens as we learn about humanity through Alex’s innocent and wise reflections.

In See You in the Cosmos, author Jack Cheng introduces us to the protagonist, Alex Petroski, who is in the middle of creating a Golden iPod that he is determined to rocket into space to teach aliens about humanity. From beginning to end, the novel is a transcript of the Golden iPod’s audio. Through this unique narrative device, we readers become the aliens as we learn about humanity through Alex’s innocent and wise reflections.

The Golden iPod narrative device is clever and draws us in, but it might quickly lose its appeal without Cheng’s deft craftsmanship. First, he uses the device to give his aliens–um, readers–an intimate portrait of his protagonist, making him a very compelling character. Next, he provides mystery and intrigue, allowing the reader to “figure out” the truth of what’s going on by sifting through Alex’s unreliable view of the world as the story progresses. Finally, he weaves in profound and wise thoughts through Alex’s innocent musings.

Drawing a Compelling Character

Recently, fellow contributor, Jen Jobart, explored Cheryl Klein’s ten strategies for creating compelling characters (The Magic Words) here. Using most if not all of Klein’s strategies, Cheng deftly takes advantage of Alex’s running monologue to paint an intimate portrait of the boy in such a natural and believable way that we can’t help but feel a strong and immediate attachment to him.

Cheng demonstrates Alex’s curiosity and strong engagement with the world (Klein’s strategy #2) via the stream of questions he poses to the aliens, despite the fact that he will never meet them. The novel starts us off with Alex’s questions and it never lets up:

“Who are you?

What do you look like?

Do you have one head or two?

More?

Do you have light brown skin like I do or smooth gray skin like a dolphin or spiky green skin like a cactus?

Do you l live in a house?” (page 1)

Whenever Alex is mulling over a subject, he imagines how it might relate to aliens:

“Maybe as soon as you love someone you’re physically connected to them with a tube that’s kind of like a leash, except it’s made out of flesh and it grows out of your belly button and you call it a fleash.” (page 109)

These musings are both charming and relatable, but only because they’ve been given an organic outlet via the Golden iPod.

Readers quickly learn about Alex’s compelling desire (Klein’s strategy #5). Even better, they learn of it in the cutest way possible when he tells his beloved dog, Carl Sagan:

“You watched me spray-paint it gold, remember? I’m making recordings so when intelligent beings millions of light-years away find it one day they’ll know what Earth was like, do you understand?” (page 7)

His excitement over his mission, his high energy and innocence, and his resilience and optimism give us a character who feels fresh and unique (Klein’s strategy #1).

“Every. One. Is. So. AWESOME.

I’ve never met so many people who love rockets and space as much as I do.” (page 59)

In addition, through Alex’s recounting of his recent interactions, we hear tidbits that confirm that people who meet him also find him to be appealing (Klein’s strategy #8).

“I told Scott that if they ever discover a new planet they should call it Public Relations so that way his team can have a planet too. Scott laughed and then he gave me some stickers.

Elisa told me she loved the OpenRocket screenshots I posted when I was designing Voyager 3 and my cheeks started getting warm, it’s a really hot day today. She gave me her business card also and she said if I’m ever looking for a summer internship, they’d be glad to have me.” (page 62)

Cheng gives his readers the sense that Alex is constantly in jeopardy (Klein’s strategy #6) by sending him on his own adventure ALL BY HIMSELF first via train and then in a car with strangers. While he blythely narrates his trip on the Golden iPod, we all anxiously assume that bad things are on the verge of happening. Every time he meets a stranger, we expect that stranger to pose a threat. Cheng uses our own biases against us to build tension. However, ironically, the people he meets are surprisingly kind and trustworthy. It’s only when he returns home that he encounters serious jeopardy, which reinforces the idea that for Alex, home, not the external world, equals danger.

This leads us to Klein’s strategy #4. Alex’s circumstances are wildly different from those of this novel’s likely reader. While a subset of children have unsafe and unpredictable home settings, a healthy majority are raised to believe that the external world is much more likely to pose a threat. Most children who read this novel will not even consider setting out alone on their own adventures. And most will not have parents with serious mental illness. Alex has a broken family in almost every way imaginable–a disappeared and likely dead father, a mother struggling with mental illness, and a negligent brother. Without Alex’s enthusiastic and optimistic Golden iPod narration, this novel could be impossibly sad. The narrative device provides us with a voice that transcends the more somber realities of Alex’s world.

Action: Experiment with narrative devices that will enhance your ability to create compelling characters.

Adding Mystery and Intrigue

Due to Cheng’s Golden iPod narrative device, there’s no omniscient narrator filling in gaps in our knowledge–whether about Alex’s backstory or what’s happening in the present. Therefore, since naive Alex doesn’t fully grasp his complicated backstory, nor the adult interactions that orbit around him, his narrative is ultimately unreliable. An abundance of mysteries about Alex’s troubled family are introduced, and the reader must figure out the truth of what’s going on by sifting through Alex’s words as the story progresses. This adds an element of intrigue that makes See You in the Cosmos compelling.

For example, early on Alex records the following:

“Plus [my mom] was having another one of her quiet days where she stays in bed and stares at all the little bumps on the ceiling. I think she likes counting them. And I brought water to her room and I told her, I made you food for the next three days when I’m at SHARF, all you have to do is take out the GladWare from the refrigerator and heat it up in the microwave and I love you.” (page 14)

The reader knows that a) 11-year-olds don’t cook for their parents all the time, b) mentally healthy people don’t stare at the ceiling all the time, and c) mentally healthy moms aren’t going to let their 11-year-olds go off on their own to SHARF (Southwest High-Altitude Rocket Festival). Because of the reader’s knowledge, they can sift through Alex’s words and deduce that his mom is not mentally well.

Likewise, readers make their own deductions when they read Alex’s innocent interpretation of one of the secondary characters’ interaction with his girlfriend:

“Steve got another call from his girlfriend and he was trying to talk to her quietly at first but then he was talking louder and louder, so he went to his car so he could talk with her as loud as he wants. And then I thought that maybe Steve can be my man in love because he has a girlfriend, and I told Zed about it and I thought I saw him frown but maybe it was just dark, because he laughed and shrugged his shoulders again.”

Most readers understand that when people raise their voices, it’s reasonable to deduce that they are fighting with each other. Zed’s reaction and Steve’s fight with his girlfriend reinforce that Steve and his girlfriend are not doing well as a couple. Therefore, they would not be a good example (for aliens) of love between a man and a woman. Since Alex is narrating the episode for the benefit of his Golden iPod (vs an omniscient narrator), there’s more room for dramatic irony.

Action: To heighten intrigue and reader engagement, experiment with narration that remains so deeply in a character’s point of view that the reader must suss out the truth of the story rather than being spoon-fed it.

Weaving in Profundity and Wisdom

Cheng takes advantage of his narrative device to sprinkle in moments of wonder and delight for the reader. For instance, when Alex and Terra talk about her love for the water, he makes it feel like a cosmic inevitability:

“… it’s more like when she’s in the water she feels like she’s in her most natural environment. I said, Oh, that makes a lot more sense, because we originally evolved from colonies of bacteria in the ocean hundreds of millions of years ago. I told her also our bodies are made mostly of water, so if you think about it, it’s like if you fill up a water balloon and put it in a bathtub full of water, then the only thing that keeps the inside water separate from the outside water is the skin of the balloon, and if the skin wasn’t there there’d be really no difference.” (page 156)

Later through his innocent musings, Alex helps us to believe that our lives are bigger than our day to day worries:

“What if the times when we feel love and act brave and tell the truth are all the times we’re four-dimensional, the times we’re as big and everywhere as the cosmos, the times when we remember, like REALLY remember, really KNOW, that we’re made of starstuff and we’re human beings from the planet Earth…” (page 300)

Action: Experiment with devices that will allow you to organically add weighted moments of profundity.

Recently a distinguished professional in the publishing industry mentioned to me that the most important thing in any book (besides voice) is to surprise and delight the reader. Using a fresh and clever narrative device not only leads the way to a fresh and clever voice, but it also gives an author a myriad of opportunities to surprise and delight.

Kristi Wright (co-editor) writes picture books and middle grade novels. Her goal as a writer is to give children a sense of wonder, a hopefulness about humanity, and a belief in their future. She is represented by Kurestin Armada at Root Literary. She is an active volunteer for SCBWI and a 12 X 12 member. Find her at www.kristiwrightauthor.com and on Twitter @KristiWrite.

excellent and informative post!!!!!