MG Lunch Break was lucky enough to have Bridget Hodder, author of The Rat Prince, attend one of our in-person gatherings on Skype. Group member Jill Diamond interviewed Bridget with questions solicited from group members. When introducing Bridget, Jill said, “She’s not only a brilliant author, she’s also a great friend and a good supporter for other authors.”

We thoroughly enjoyed our conversation with Bridget, and we’re happy to share some of her experience and wisdom here. What follows is an edited version of our conversation. (Also see a craft review of The Rat Prince here.)

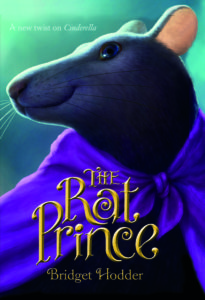

Before Cinderella’s stepmother and stepsisters moved into Lancastyr Manor, Cinderella was known as the Lady Rose de Lancastyr. Then her stepmother forced her to become a kitchen maid and renamed her. At first the rats of the manor figure Cinderella for a lack-wit and take pity on her by bringing her food and a special family heirloom. But when Cinderella’s stepmother finds a way to prevent her from attending the ball, the rats join forces to help her. The night of the ball is filled with magic and secrets–not least of all who Lady Rose will choose to be her Prince Charming.

KidLit Craft: You certainly have a love for your rats in your book. Have you ever had a pet rat?

Bridget Hodder: I have not. In fact this was kind of an exercise for me in overcoming a little bit of a fear that I had of rats [from childhood]. I feel like this fear helped me keep a kind of wild-animal edge to Prince Char. There’s always going to be an element of fear dealing with rats, even when you’re dealing with a sweet pet.

You mentioned in an interview that you left some inaccuracies about rats in the story. What are those inaccuracies, and why did you leave them in?

[I was able to pose questions to a rat expert.] I had questions about the real deal on rat anatomy. The sticking point was rat hands versus rat paws. They’re not paws. They’re more like hands. They have actual fingers, and they can grasp things. But my editor thought, and I came to agree with her, that it became confusing when the rats were sharing scenes with humans. Hands and fingers were doing things, and it wasn’t readily clear whose digit or whose appendage was whose.

If anyone ever brings it up, it’s a great talking point: why would such a choice have been made? [The discussion can] point them to looking into it further, finding out the truth about rats.

How did you decide what parts of the original Cinderella story to keep?

I wanted to stick to the basic outlines of the original story and not really fracture it. I don’t consider this a fractured fairy tale. It’s a reimagining, and I took it deeper. I wanted it to be like something that really was the truth, but had been withheld from us, for good reason, and was now coming out. And for that reason, the circumstances in which I placed these characters were pre-existing for the most part. There were different scenes that arose from the changes that I made.

But I tried to answer the big questions: Why did they need to throw a ball for the Prince to choose a bride when he’s a handsome crown prince? What was wrong with him? And what was wrong with Cinderella’s dad that he let somebody come in and turn his daughter into a servant? And why did the daughter let herself be turned into a servant? Why would she say OK to that and not fight back? Or at least try? Why would she sort of cower in that way? It never made sense to me. I felt that in a non-anachronistic way you could look at it and say, “Wait a minute. Why? There’s something missing.”

How did you choose Lady Rose’s age?

It’s a good question. I had to think about [her age], because she ends up getting married at the end. I really needed Cinderella to be old enough for informed consent, and young enough to still be in that groove of somebody who really hasn’t come into her power yet at the beginning of the story. [She needed to be] someone the readers could identify with. I thought sixteen was a little bit young for modern readers to feel comfortable with her getting married, so seventeen was better. I felt I had to maintain the historicity of having people who marry quite young, because people had fairly short lives back in the in the day.

Talk about the beheading scene. Did you get pushback on that?

On the beheading scene, the editors were concerned because it’s a middle grade story. My first thought was . . . this kind of thing shows up a lot in fairy tales. Take “Hansel and Gretel.” The story is basically: We are going to be cannibalized, and in order to prevent that we’re going to push this woman into an oven, close the door on her, and let her die. So, quick references to gruesome violence aren’t uncommon in these stories.

I felt that the beheading in The Rat Prince was so important, not just as a piece of a fairy tale . . . It was also a pivotal moment. It’s the moment when everything changes. Not even the moment when Char became human, along with Swiss and Truffle, was as pivotal. [The beheading is] when suddenly everyone realizes that the things they were assuming about Prince Tumtry, and the ball, and the future of Angland, are not actually what’s going on. The stakes have suddenly been raised way beyond anything we were considering before. Without the beheading, there’s no reason for the crazy urgency that the whole rest of the evening has for Prince Char, who cannot communicate this to Lady Rose [because the fairy godmother figure forbids it]. Stakes are high for Lady Rose, in her own mind, but if she knew how high the stakes were, she would stay home. That wouldn’t be the Cinderella story as we know it; it would completely break apart all of our expectations in a really dull way instead of in a really interesting one. From there on it’s a race against time to the end of the book.

I think in all writing, first you need to engage your readers. You need to make them really care about what happens to the characters. Then you need to make [the readers] hope for a particular outcome for those characters. And then you need to put that outcome very much to question. You need to put them in danger and their goals in danger.

I felt like without this extreme example [of the Prince’s behavior], that maybe Char would have just been seen as overreacting or being hyper.

The narrator’s voices are pitch perfect in The Rat Prince. Can you talk about how you found your way to them? Did the two voices that come to you once, or did you find them through revision?

Thank you for the compliment! [The two voices] were distinct from the get-go. For me, when I start to write, I really need to know who the characters are before I use my fingers on the keys because I think plot falls into place once you have characters who are super real. You feel as if they’re friends or enemies you know personally . . . and then you’ll know how they would react to certain circumstances. And that way they’re consistent, just like before you call your mom and tell her something, you already know exactly what she’s going to say about it (which means you may not bother to call her at all). You know what your characters are going to do or say. [Because I knew my characters,] I never had to wonder. I was able to put them in the structure of the Cinderella story and let them be themselves.

How did you decide to use both points of view? And could you talk a little bit about alternating point of view in each chapter? Do you feel that a two-protagonists story must alternate chapters, or was it the right choice for this particular story?

It really felt from the beginning that it had to be told this way logically. I didn’t want to do third person. It felt “talky-downy” somehow. I felt like the reader needed to engage at a different level.

The first person alternating had to happen because Char and Rose were characters who occupied completely different spaces within the same universe, and would not come together and be in the same scenes until the second half of the book. People needed to know rat history, rat lore, rat customs. And they needed to see Prince Char in action with his friends and his family. (I loved to be able to keep a mother and a father in there. There are all these narratives where it seems like the requirement is that the parents be dead, or that mothers can’t be strong and yet also benevolent, intelligent characters with guidance to offer. I really enjoyed writing Lady Apricot and keeping her alive through the book.)

And we need to hear Lady Rose’s internal thoughts because her actions were so different from her plans in the beginning. And it was an explanation of why she appears so passive in the original. She’s not passive, and that’s what we hear in Chapter 1: she’s biding her time.

How long did it take you to write this book, first idea is to publish copy?

It took me six months to write The Rat Prince from idea to finished manuscript. But that was an incredible six months where I did nothing else. I mean literally; I was possessed. I had to wear gloves on my fingers because my fingertip nerves were hurting. I got tendonitis in my elbows. I had to prop my hands up with pillows. I was writing from 6 a.m. to midnight, except for carpool. It was an intense six months. And I was lucky to be able to do it that way.

Once the book was sold [to Macmillan/FSG], it was a very long process. But that’s fairly typical for a debut. The average publication time for a new author’s book to come out after it’s sold is about two years.

Can you talk a little bit about the revision process? Of the six months that you spent writing the book, how long did you spend actually revising, and how many of revisions did you go through?

I’m one of those funny people who revises as she goes along. When I finish the chapter, I can’t go on to the next chapter, and sometimes even to the next scene, until I’ve made the last one perfect. I know that that really goes against what everybody says you’re supposed to do, but everybody’s different. There’s a lot of good advice out there, and you need to find out which of it works for you personally.

[When I’m writing], I need a reason to go on to the next scene. I need to stop each scene at a high point that’s going to propel me to turn the page. Otherwise I’m not enjoying writing it, and I feel like that has to happen or people aren’t going to enjoy reading it.

When I finish a chapter and it doesn’t satisfy me, I go back in–I want to really make it pop, I [want] to really understand everything everybody says.

So by the time I got to the end of The Rat Prince, what remained for me to do was polishing, re-reading the full, and making sure that everything flowed from scene to scene, chapter to chapter, where I wanted it to. And honestly that didn’t take very long because I had done the work beforehand.

I did my agent submissions the traditional way: I wrote query letters, and I got requests. And once I had my agent, he had a couple of suggestions. I actually had written an epilogue where you find out what happens to everyone. But my agent said, “You’ve got to cut that epilogue. You have to leave this up to people’s imagination.” He was right, of course. So I took that out and then it went on submission.

My editor at Macmillan/ Farrar, Straus & Giroux really did an amazing job of tightening and toning the manuscript, and taking care of a thousand details (like continuity and things that didn’t make sense). It was so much better after she was through with it!

Thanks, Bridget! It was really fun to hear you talk about the book.

It was really an honor.

COMMENTs:

0