craft review by Jen Jobart

In Chapter 6 of his book The Anatomy of Story, John Truby talks about building a story world that reinforces the story you’re telling. Jessica Townsend’s book Nevermoor: The Trials of Morrigan Crow is a great case study for how to do this.

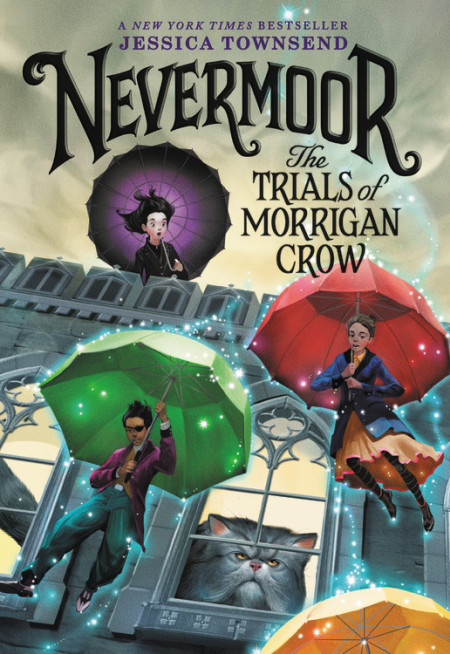

Nevermoor is the story of Morrigan Crow, a cursed child and daughter of the Chancellor of the Wintersea Republic. She expects to die on her twelfth birthday, the expected dawn of the New Age. However, when the New Age begins a year early, Morrigan escapes the Republic with the jaunty Jupiter North, a man from the Free State who has sponsored her as a pledge for the Wunder Society. Morrigan hasn’t heard of the Free State or the Wundrous Society, but passing the four trials to become a member is her best chance for staying in the Free State and escaping from the torturous life she had in the Republic.

Townsend uses Truby’s described “fish out of water” technique to show that Morrigan was an outcast in the Republic for the same reasons that made her a hero in the Free State. Townsend uses Morrigan’s house in the Republic as a contrast to the Hotel Deucalion, her home in the Free State, to reinforce the story. Octavia the arachnipod makes a delightful passageway in between.

Morrigan’s house in the Republic: the Terrifying House

In The Anatomy of Story, John Truby writes, “When the terrifying house is a grand Gothic hulk, an aristocratic family often inhabits it. The inhabitants have lived off the work of others, who typically dwell in the valley below, simply because of their birth. The house is… too empty for its size, which implies there is no life in the structure. In these stories, the house feeds on its parasitic inhabitants just as they feed on others.”

Morrigan’s home in the Republic is a perfect illustration of the Terrifying House.

The Republic is a dreary, competitive, political environment. Everyone tries to be someone others will like, rather than being true to themselves. They blame cursed children for their own mistakes.

In the Border Towns, a scarcity of Wunder is causing power outages and discontent. Meanwhile, the Capital has more than enough Wunder. Corvus Crow, Morrigan’s father and the Chancellor, keeps firing his advisors because they are all telling him that people are increasingly dissatisfied with his selfish, hands-off approach to leading.

Morrigan’s house is empty of people and of love. Her mother has died. Her father is preoccupied with his job and finds his daughter to be mostly an inconvenience. Her stepmother dislikes her, and is plotting to have more children as soon as Morrigan conveniently dies. Her grandmother is largely absent.

At the beginning of the book Morrigan’s home in the Republic seems safe. Leaving it seems scary. But by the end of the book, the risks have swapped in Morrigan’s mind and the Hotel Deucalion seems much safer than what she left behind.

Hotel Deucalion: the Warm House

Truby notes that “the warm house in storytelling is big (though usually not a mansion), with enough rooms, corners and cubbyholes for each inhabitant’s uniqueness to thrive. Notice that the warm house has within it two additional opposing elements: the safety and coziness of the shell and the diversity that is only possible within the large.”

Hotel Deucalion epitomizes the Warm House.

In contrast to the Republic, the Free State is a magical, hopeful place where anything is possible. Everyone is unique for their own sake. There are plenty of resources for everyone. Disasters don’t happen as often, and when they do, they aren’t blamed on cursed children.

Morrigan’s introduction to the Hotel Deucalion, with the rooftop party to celebrate the New Age, has people and animals and other magical characters all celebrating together with a pink champagne fountain. Everyone is taking risks, and at the culmination of the party everyone jumps off the roof with the refrain “Step boldly!”

The Hotel Deucalion is a living being in itself. Morrigan’s bedroom adapts to her as it gets to know her better. The chandelier falls out and regrows to better suit the inhabitants. There are thirteen floors; they are the opposite of superstitious.

The Free State could not be more different from the Republic.

Octavia: the passageway in between

“Anytime you set up at least two subworlds in your story arena, you give yourself the possibility of using a great technique, the passageway between worlds. A passageway is normally used in a story only when two subworlds are extremely different. We see this most often in the fantasy genre when the character must pass from the mundane world to the fantastic. … A passageway has two main uses in a story. First, it literally gets your character from one place to another. Second, and more important, it is a kind of decompression chamber, allowing your audience to make the transition from the realistic to the fantastic. It tells the audience that the rules of the story world are about to change in a big way. The passageway says, ‘Loosen up; don’t apply your normal concept of reality to what you are about to see.’ …A passageway is a special world unto itself; it should be filled with things and inhabitants that are both strange and organic to your story. Let your character linger there. Your audience will love you for it. The passageway to another world is one of the most popular of all story techniques. Come up with a unique one, and your story is halfway there.” –John Truby, The Anatomy of Story

Jessica Townsend does a brilliant job describing the passageway in Nevermoor. It’s worth reading over and over again to understand how she does it. I’ll just recap the basics here.

First, the contract shows up in Morrigan’s room. She signs it and throws it in the fire, but then Jupiter shows up at her door anyway. He tricks her family into believing that the curtain is her dead body. The Hunt shows up to pursue her. Morrigan and Jupiter climb to the third floor, and Jupiter tells her to jump out the window to his arachnipod, Octavia. Octavia exits the Republic through the clockface. They go through customs, which is a hilarious farce. Finally, they enter Jackalfax and the Free State.

Octavia literally takes Morrigan from one world to the other, and in the process, she experiences Jupiter North’s quirkiness and the unexpectedness that comes in entering a magical place she didn’t know existed.

My takeaways

I’m about five drafts in to my WIP. I was thinking that I was getting close to being ready to query it. And then I read The Anatomy of Story.

Truby’s chapter on Worldbuilding, and his chapter on Moral Argument, (look for a companion post on the Moral Argument of Nnedi Okorafor’s Akata Witch) were game changers for me. They helped me to realize that there is more I can do to make my novel even richer. I think that the building blocks are there; by making sure there was both an external plot and that my main character had an internal journey, I set the story up right. And I think I instinctively scratched the surface on lot of this.

But reading these Truby chapters, and deeply studying two master works that do this well, has shown me that my story isn’t finished yet. There is more I can do to make sure that everything in the book’s world supports the story I’m trying to tell. There is more I can do to make sure that my theme is reflected by all of my characters, and in all of the key scenes.

So I’d better stop working on this blog post and get back to my novel! I hope that this helps you in some way, too. Let me know what you think in the comments.

Jen Jobart writes middle grade fiction and is always sending characters she loves on dangerous adventures. She is an active member of the SCBWI and has studied writing for children through Stanford’s Continuing Studies program. When Jen’s not writing, she’s outside gardening and raising chickens at her home in the San Francisco Bay Area. Find her at www.jenjobart.com.

COMMENTs:

0