craft post by Kristi Wright

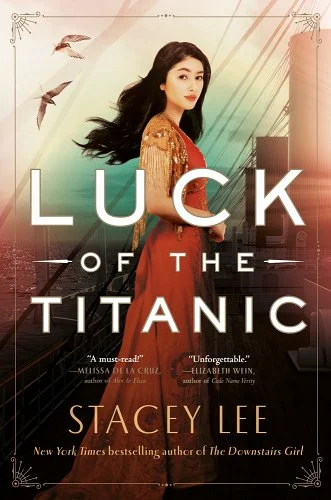

Author Stacey Lee knows better than most how to delight her legion of fans with historical YAs that shine a light on people in history who have often lived in the shadows. Her latest novel, Luck of the Titanic, is inspired by the eight Chinese men who were on that ill-fated voyage. One of the things I admire most about Lee’s storytelling is her intentionality when it comes to the language she uses. She doesn’t just write pretty sentences (though they are very pretty). Her prose always serves the story. (See our interview with Stacey Lee.)

Since Lee uses first-person point of view to tell her stories, it’s her main character’s voice that’s in the driver’s seat. Reading her novels is a masterclass in how to do first-person narration well. However, you can use these techniques with third-person and even with omniscient narration. It’s all about elevating your prose to do more than just tell the reader what’s happening.

And from the very beginning, we see how Lee leverages specific language to develop character. The protagonist Valora Luck’s name shows us who she is, reinforcing that she will show valor (great courage in the face of danger) and either be supported by good luck or thwarted by bad luck.

Developing Character: What Drives the Protagonist

In the opening paragraph, Valora introduces herself and her intent to chase down her brother, Jamie, thus establishing herself as highly determined.

When my twin, Jaimie left, he vowed it wouldn’t be forever. Only a week before Halley’s Comet brushed the London skies, he kissed my cheek and set off. One comet in, one comet out. But two years away is more than enough time to clear his head, even in the coal-thickened air at the bottom of a steamship. Since he hasn’t come home, it is time to chase down the comet’s tail. (1)

Lee’s decision to use Halley’s comet both to establish the timing of Jamie’s departure and as a metaphor for him is a clever one. In the early 1900s, many people still saw comets as harbingers of disaster. (In fact, historians have noted that the Chief Designer of the Titanic observed Halley’s comet during a visit to the Titanic while it was still under construction.) Whether readers know the information behind the metaphor, they will understand how Valora’s use of the metaphor emphasizes her clear goal and her determination.

One of my favorite lines in the novel encapsulates Valora’s intent using a delightful ship-related metaphor:

I’ll keep tugging little by little, and like the boats that coaxed the Titanic to sea, eventually I’ll get Jamie to budge. (81)

There isn’t a hurdle Valora won’t climb, jump over, or knock down to get what she wants, and Lee gives Valora ample opportunity to show how determined she is in her interiority and actions.

Setting Descriptions that Reveal Character

Lee’s setting descriptions add to readers’ understanding of Valora as a character. When Valora sees the boiler room for the first time, she’s reminded of dragons, mythical beasts that are deeply connected to her Chinese heritage.

From my perch on the ladder, I see four grinning black dragons standing shoulder to shoulder, their triple furnaces blazing like two eyes and a mouth. Trimmers cart coal in wheelbarrows for the firemen to feed the dragons, while others sweep the floor plates or monitor valves and pipes and pulleys and, well, things I don’t have a name for. It’s another universe made of iron and fire and sweat and sinew, and, yes, light. (153)

Juxtaposed against the boiler room dragon’s lair, is Valora’s first-class room. Lee uses Valora’s life experience as an acrobat to help readers fully grasp how spacious it is.

In the bedroom, a Persian rug tops wall-to-wall carpeting. The room is wide enough for me to cartwheel and flip over in one run, if not for the center table. (57)

Because we see the world through Valora’s eyes, we get to know more about her. We don’t just know from telling that she has acrobatic skills. No, she measures the size of a room through imagining herself tumbling across it.

When Valora arrives at the A-Deck, her life experiences make her sees the opulence differently than the other first-class passengers might:

The lift takes me as far as it can, to A-Deck. The cherub standing at this highest leg of the tidal-wave staircase is even chubbier than the ones below. I climb past nobs in their finery toward the Boat Deck. At a half landing, more divine types loiter, including two angels holding in place an elaborate clock that reads 8:40. The afterlife certainly features prominently in the decorating here. But is a vessel in the middle of the ocean really the place to be constantly reminded of death? (76)

She sees that here in the opulence of the first-class world, the cherubs are chubbier (well-fed). She refers to other first-class passengers as “nobs in their finery.” Nob is a term that conveys contempt for the rich and powerful. Valora thinks of the angels in the decorations as representing the afterlife, which to her translates to being a reminder of death.

Her experience of space and setting and her interpretations of it reveal to us how Valora sees the world, adding depth to her character.

Sensory Details that Reveal a Character’s Emotional State

Lee chooses sensory details that matter, whether because they grow readers’ understanding of Valora’s emotional state or they act as reminders that a tragedy is on the horizon.

Early, when Valora’s still a stowaway, Lee uses sound to evoke Valora’s feeling that she’s a fox on the run.

Three stout notes, blown from somewhere above, form a chord that rumbles through my body. The floor begins to move as the ship sets sail. The trumpets that herald us out to sea remain in my ear, sounding more like the howl of the hounds when the fox slips through their grasp. (27)

When Valora finally sees her brother for the first time in two years, she is overcome by how his scent is both familiar and changed:

I embrace my brother. The familiar scent of milk biscuits and trampled ryegrass, now dusted with coal, puts a lump in my throat. (38)

One of the things Valora has to learn in Luck of the Titanic is that her brother isn’t the same person she knew growing up. That he has his own path, with his own desires. The first moment when she sees him again encapsulates the idea that he has evolved since last she saw him.

In addition to evoking emotions with sensory detail, Lee also uses sensory details as foreshadowing, reminding readers that the Titanic is heading into ice fields. Since readers will likely know the role lifeboats played in the Titanic tragedy, having Valora see them and imagine them as a possible safe haven is both ironic and tugs at our readerly heart strings.

I twist to my left, glancing across the well deck toward the top of the superstructure and the lifeboats that ring the perimeter of the Boat Deck. If all else fails, I could sleep in one of those. Of course, I would need to grow a layer of blubber to protect me from the freezing nights. The Atlantic will be as cold as snowmelt, maybe even colder, once we reach the ice fields off Newfoundland. (31)

Lee doesn’t just offer up a sweet scent or an icy touch. She ensures that readers have enough information so they can connect the dots about why a particular sensory detail is important.

Cultural References that Bring Depth and Authenticity

Lee’s Chinese cultural references show how Valora’s roots have defined her and also add authenticity to the historical nature of the story.

For instance, Valora and Jamie being twins has special meaning in Chinese culture. Valora explains:

In China, A dragon-phoenix pair of boy-and-girl twins is considered auspicious, and so Ba bought two suckling pigs to celebrate our birth, roasted side by side to show their common lot. Some may think that macabre, but to the Chinese, death is just a continuation of life on a higher plane with our ancestors. (3)

The following additional reference to their twinness by one of the Chinese seamen is both culturally rich and deeply emotional and reinforces Valora’s understanding of her relationship with her brother:

“When Jamie told us his twin sister was here, Tao was not surprised. He said twins always come together like ginger and garlic. They can stand by themselves, but they are always meeting in the same dish.” (151)

Lee also effectively weaves in the Chinese distrust of the number four to amp up tension over the Titanic’s doomed voyage:

The benches are empty with few people about, most finding better fun inside the ship. Electric lights cast an eerie glow around the smokestacks. The fourth and farthest one does not smoke. Perhaps it is only for show. The Chinese avoid the number four, but Westerners like even numbers.

The lifeboats stand pale and motionless, ghostly cradles held by skeletal arms. Four in each of four corners. I shiver. This deck is full of bad luck, and I bet Fong would steer clear even if he was allowed up here. (77)

Lee doesn’t just throw historical research at her novel willy-nilly. She picks the elements that serve her story best.

Observations that are Unique to Valora

Valora’s first-person narration is filled with observations that are beautiful to read while still being subservient to the story.

Because Valora straddles the first-class and third-class worlds, she’s uniquely positioned to compare and contrast them.

People here sail around as if they have all the time in the world, unlike in the third class, where one is not wasteful even with time. (51)

Valora reveals much about her inner demons in this interiority:

The dark is an old enemy. It doesn’t bother me so much when others are around, like the Sloanes’ cook, with whom I shared a room. But when I’m by myself, the dark waits to ambush me, so I won’t give it a chance. (63)

Given everything the reader already knows about the Titanic, the following sentence is an extraordinary harbinger of doom. I love Lee’s use of “drowning” in this context:

The ocean gulps and shushes, drowning my voice. (77)

And when a steward delivers flowers to Valora, while under the mistaken impression that she’s a first-class guest, Valora sees something very different from what most characters would see:

The lilies seem to cough at me out of their scarlet throats. The real Mrs. Sloane, with her limited vision, would’ve appreciated those heavy scenters, but they remind me of the cemetery. (88)

Throughout Luck of the Titanic, Valora’s narration does more than just tell the reader what’s happening. It deepens readers’ understanding of what drives her, what her emotional state is, what she sees and how she perceives it, creating a fully fleshed-out character we can root for.

Now it’s YOUR turn . . .

- Readers love characters who are actively pursuing their goals. Check for what drives your protagonist. What can you do to reinforce your MC’s intent?

- Look to setting descriptions for opportunities to reveal more about your MC’s view of the world.

- Let sensory details reveal something about the MC’s emotional state.

- Consider whether you have a layer, such as an MC’s cultural roots, that you can lean into to add authenticity to your story.

- Finally, find opportunities for your MC to have unique observations that are fun to read.

In case you missed it: our interview with Stacey Lee

And our own Kat St. Clair finds inspiration from Stacey Lee’s writing process: Confessions of a (Not-So) Reformed Pantser

Kristi Wright (co-editor) writes picture books and middle grade novels. Her goal as a writer is to give children a sense of wonder, a hopefulness about humanity, and a belief in their future. She is represented by Kurestin Armada at Root Literary. She is an active volunteer for SCBWI and a 12 X 12 member. Find her at www.kristiwrightauthor.com and on Twitter @KristiWrite.

COMMENTs:

0