hello!

JOIN US IN EXPLORING OTHERS' CRAFT AND BUILDING OUR OWN

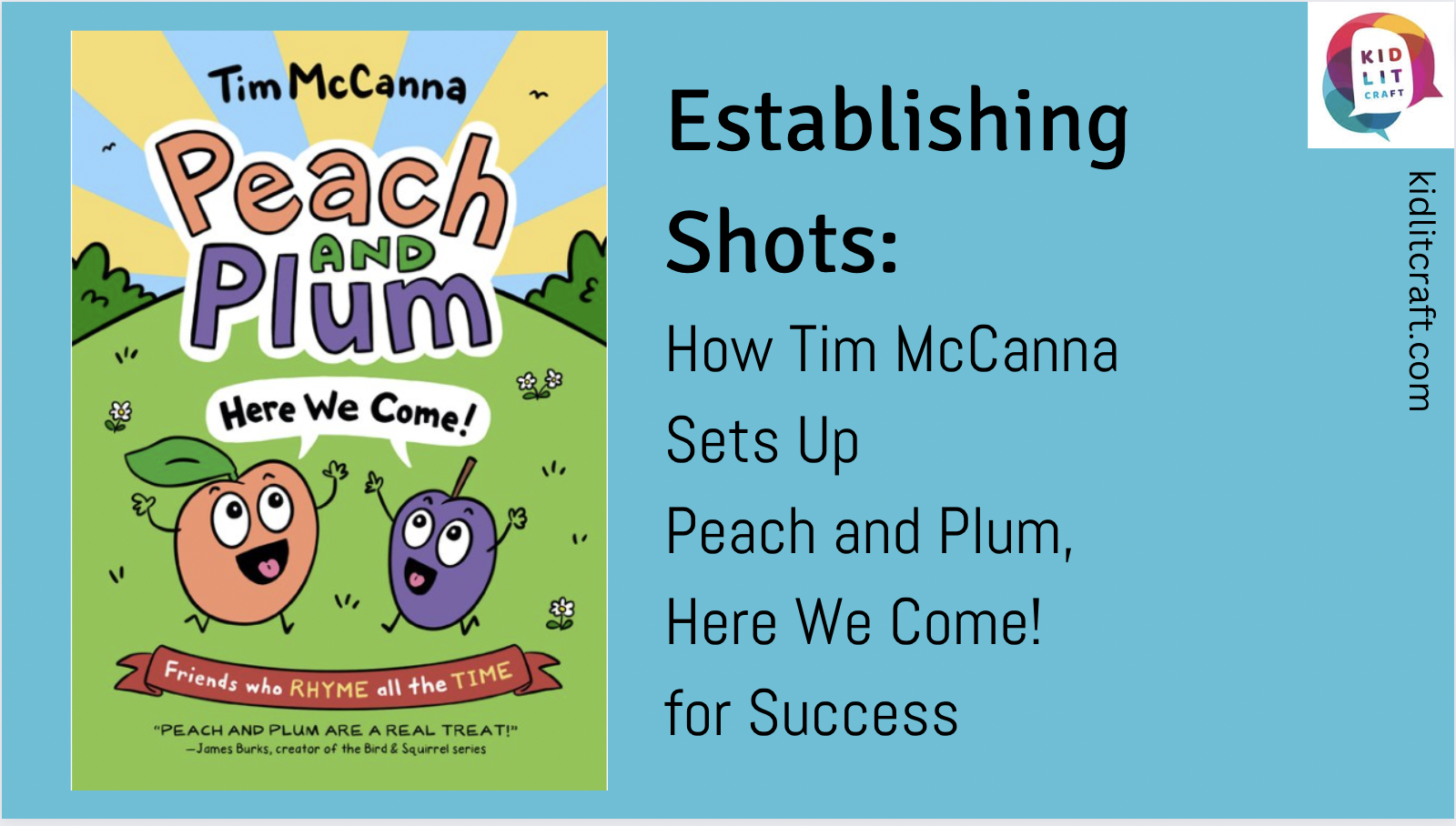

In order to get early readers on board, Tim had to draw readers in from the very first page and show them what to expect from the book. His 38-word, two-spread introduction to the book is a master establishing shot that covers not just setting, but all the elements readers need to be pulled into a story.

Place matters. A story set in Paris can be transported to Atlanta, but the story fundamentally changes because of the geography, culture, language, idioms, weather, daylight hours, experience of time, and so much more. These posts explore how to establish settings and leverage them to enhance the reading experience.

A lot of people want to be allies, or seen as friendly and open to the idea of friendship across races, cultures and social strata. This idea of “just talk to each other” may seem like it’s wildly oversimplified, but it turns out that if you want to know someone, it really is that simple. You may be nothing like a diehard gardener or wide-eyed tween, but if you’re willing to see a potential connection between the two of you, it will be there.

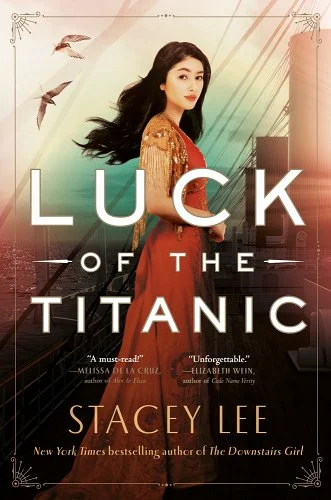

Since Lee uses first-person point of view to tell her stories, it’s her main character’s voice that’s in the driver’s seat. Reading her novels is a masterclass in how to do first-person narration well. However, you can use these techniques with third-person and even with omniscient narration. It’s all about elevating your prose to do more than just tell the reader what’s happening.

Empathy has its drawbacks, especially when reading the news, but on the plus side, I think it helps me create deeper characters. The secret for creating unforgettable characters is to give them impossible choices.

Rita Williams-Garcia masters the crowd scene–a dinner at the midpoint of the book. In a movie, it’s easy to see the crowd and feel the energy in the room. In fiction, it’s more complicated–you need to balance the minute and individual with the group so that readers feel grounded in the environment and in the particular characters’ interactions.

I fully transport myself from my reality into the world that I seek to create. In a word, I daydream. Deeply. I put myself with the character, close to the character, sometimes in the character, to taste the dirt when they’re in the dust storm or feel the scratchy bristles of cane stalk whip my face. Then I write it. Later, I make adjustments, because what I have to understand is different from what the reader should feel. Sometimes I have to rein it in or pull back. It’s not always the point that the reader should feel each and everything—but the writer must!

As writers, we can look to our settings to provide a wealth of tools to not only add depth to the story but to underline the experiences of the characters, their feelings, their motivations, their desires.

The authors and contributors we interviewed had so many wonderful sidewriting challenges, we thought we’d put them all in one place. Each exercise will have a link back to the original post so you can learn more about the author and how sidewriting works for them. Enjoy!

Evan Griffith: There’s usually a long period of exploratory writing after I get an idea and before I begin drafting. I’ll write random scenes, character studies, letters from my character to me, and so on, all to get a feel for the mood, tone, and style of the story. If the story takes shape through these exercises—and, crucially, if it holds my interest—then I feel more confident going into the drafting process.