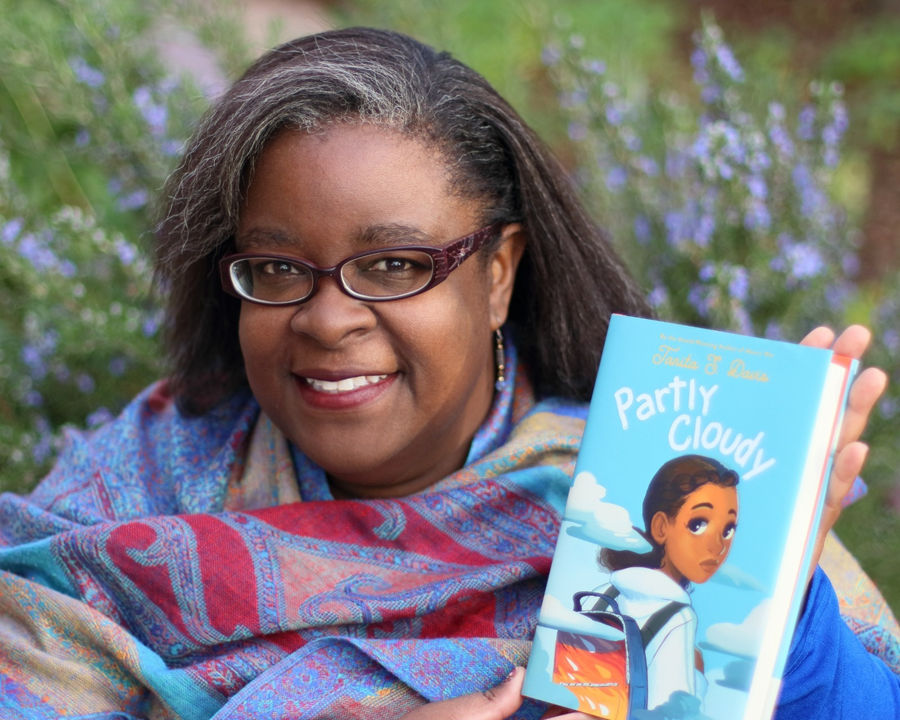

It was such a pleasure to read the latest novel by award-winning author, Tanita S. Davis: Partly Cloudy. With characters to fall in love with and a nuanced portrayal of human nature, it had me rooting for main character, Madalyn, while also encouraging me to think through what it means to be a friend, and even how I might be a better one. Davis’s writing abounds with craft, from her extended metaphor, which we will explore in more depth in next week’s craft analysis, to her delightful details, to her relatable characters. We had so much fun talking craft and inspiration with Tanita S. Davis. Enjoy! – Kristi Wright

KidLitCraft: In other interviews, you’ve talked about being inspired to write Partly Cloudy in the aftermath of the civil rights protests of 2020. When news outlets and social media suggested that white and Black people should just talk to each other, you realized that a lot of people wanted to be friends, but didn’t know how. How did you go from that spark to Madalyn Thomas’s story?

Tanita S. Davis: There’s a scene in Partly Cloudy where Madalyn meets Papa Lobo’s neighbor, this kind of over-the-top gardener who is very much A Lady, and yet who wishes death on squirrels and cats and all sorts of things because they interfere with her flowers. Madalyn doesn’t really know what to do with her – an older lady who strides onto the street like an actress onto a spotlight is completely outside of her experience – but she’s fascinated. She’s interested. She’s open to seeing where the adventure of this new person takes her. This neighbor character is taken from a real life, over-the-top teacher I had.

A lot of people want to be allies, or seen as friendly and open to the idea of friendship across races, cultures and social strata. This idea of “just talk to each other” may seem like it’s wildly oversimplified, but it turns out that if you want to know someone, it really is that simple. You may be nothing like a diehard gardener or wide-eyed tween, but if you’re willing to see a potential connection between the two of you, it will be there.* This is the truth underscoring friendships between young people and older adults, beginners and pros, try-ers and failures. If we can recognize something in each other – see ourselves in someone else? We’ve found the knot in the fence between us. That’s the “how” in the “how to be friends” question.

*This is not to say that just talking to someone will make you insta-besties. I think it’s important to note this; a lot of people don’t understand that it’s not just one conversation, but putting in the work of creating a relationship of listening and speaking in reciprocity.

KLC: Your metaphor of Partly Cloudy seemed to fit so much of this particular slice of Madalyn’s life. Which came first–the metaphor or the plot? Did Madalyn’s mom always use weather metaphors in her own speech, or was that something you added later? Can you share any tips for how to craft and manage a metaphor that spans an entire novel?

TSD: The title and metaphor arrived nearly at about the same time; the plot was from another project entirely. I had a story I wanted to tell, about friendships and what to do through the bad spells and it didn’t sell (it had some other elements and probably had too many, to be honest). I hit on the idea of aging down the original story and highlighting the friendship between an older relative and a younger one while leaving out the other details. The metaphor was just dropped in once or twice – the title, and maybe one mention of weather – and then I carried on with the story.

Once I finished I began my usual “Surgical Revisions” – as opposed to the small, constant bandage-and-painkiller level of revision I do every day. I tried to look at the big pieces that drew my eye – big themes, big takeaways, big directions that the protagonist moves. I layered in scenes to highlight that, and deleted bits that took away from those themes – and that’s where I polished up the metaphors and began to tie them together.

KLC: You have a lovely way of weaving in interesting details that bring your stories to life–Papa Lobo’s rooster collection that came with the house, the plastic-covered floral couches, the ancient hard candy, etc. Your specific details bring a scene to life. How do you go about crafting your details?

TSD: Thank you. I think it’s one of the gifts of being an introvert; observation. All of those details – the plastic couches, rooster, the ossified candy – come from the homes of elderly relatives and friends of my grandparents as a child. I don’t have notebooks of impressions or anything (how useful would THAT be?!) – but I tend more to remember how I felt in a particular moment, and color in details that lend themselves to that. I remember feeling kind of entombed alive in those still, dusty, dim rooms, trying to remember to cross my legs and sit like a lady, even though I was being laminated to plastic. I remember feeling out of my depth and wanting to hold onto my mother like a much younger child. I think Madalyn feels all of that – even as she feels a welcome at the base of all that dust and bad wallpaper.

KLC: Madalyn felt very real to me. Her struggles, her emotional journey. How do you go about creating a relatable adolescent character with real problems and emotions?

TSD: Thank you, I’m so glad Madalyn felt real. And, in your question I think you’ve encapsulated the answer: a relatable adolescent character with real problems and emotions is the key. Emotional resonance is a lot of what makes a character real.

Madalyn became more and more real for me as I grew more and more stressed at what was going on in the world… I kept thinking of how actual seventh-graders were having to cope hearing someone’s last, gasped words on camera, witnessing marches and counter-protesters shouting and driving into crowds and how all the hatefulness in the world could feel like it was distilling itself down into a classroom and a girl you thought was your friend, but maybe you didn’t really know her if she thought that about you.

Junior high is such a time of feeling shoved out, unfinished, into the spotlight of adolescence, of wanting to feel included and seen and embraced in all of our weird, chaotic, incompleteness, and imagine if there are suddenly all of these chasms emerging between people and groups once familiar and safe, and crossing these deep divides seems fraught and dangerous. The alienation of “do I really know you? Do you really know me?” would be intense.

Those are the same chasms that stood between me and the rest of the world when I was in junior high. Our problems are different, perhaps concerns and questions I had as a tween could be figured out with a few minutes of quiet and Google. But, the emotions are the same. The humanity is the same. It’s a balancing act – kids today aren’t you or me, our time as tweens is finished. But if we can imbue our characters with the same humanity and emotions we had, we respect our readers enough to relate to them.

KLC: What’s your writing process? Are you a plotter or a pantser or something in between? When do you know you have a story with legs?

TSD: I’m a Pantser who occasionally moonlights with the National Association of Pretending to Plot. I would love to have a brain that works in a linear fashion, I would love to be a person who is logical and measured and … nope.

My writing process is straightforward. I get up in the morning, turn on the computer, read what I wrote and start deleting sentences and polishing up word choices of what I wrote the day before, and then I sort of start remembering where I wanted to go, and write forward. When I begin a project, with the obvious exception of the polishing up from the day before, it’s much the same. When I’ve nailed down the narrative arc, I ask myself if I went where I wanted / expected to…. When I’m stuck, I try to outline. It helps, sometimes. Somewhat, but other times I simply try telling myself the story of what happened in an elevator pitch style. If I can’t explain an idea I have to anyone else, if the characters seem purposeless, then it needs to go back into the drawing board, or I need to quit for the day and read.

I read daily, and I read a LOT. I think good reading begets good writing, but you never know what “good reading” means for you that day. What it doesn’t mean is The Best Books For… xyz. All books are the best books as fodder for the giant processing mill that is my brain. I think it’s important for writers in the children’s lit field to know who else is in there, and who is writing and delving into interesting things, but you don’t necessarily just have to read children’s lit, either.

On good writing days, I like to write for three or four hours – on an exceptional day, I write for six. And, not to continue to yammer on about emotions, but for me that’s how I know if a story project has legs – if it offers an emotional invitation and I feel like I must take up that invitation and create a relationship. Writing realistic fiction especially has an immediacy and urgency for me to explore a question or an idea with a character – I begin to dig into something from the character’s point of view and I just feel a click like, “Yes, there’s the key opening the gate.”

KLC: In an interview with The Nerd Daily, you said: “In Partly Cloudy readers can expect a story about the real challenges of being friends across different classes and races in a way that is respectful to everyone and has a repeatable example of a way to bridge the distances between us as human beings.” I loved this aspect of your novel. It really felt as if it achieved what you intended. Do you have any thoughts on how to craft middle-grade books that model positive relationships without being preachy or unrealistic?

TSD: The idea of a “repeatable” example is what is really important in modeling positive relationships without being preachy. Anything I tell you is something that I, the author, have found useful. And if I can do it, you can do it. I don’t want to give any child (or person) advice that I haven’t used myself. Until we are able to be real about our own limitations and shortcomings, I just don’t think we can write genuinely and organically, and I don’t think we can give advice that doesn’t come from a place of judgment. That’s a lot to sit with, I know.

Like any kid, I grew up with people telling me to do this or that to be good, or to be the best at something, or to be happy, whether at church or elsewhere. Adults were full of what I should do but never how to do it. And I was a really literal child, who managed to grow up into a really literal adult. I want to do the right thing! I want to make everyone happy! Just tell me how! And for the kids who are a bit like me, I wrote a book that had a girl thinking seriously about “What makes a friend? What should I put up with? What do I need to step away from because it’s not right?” because those aren’t the sorts of step-by-step examples that we spend a lot of time on outside of recipes. Adults joke a lot that adulting or parenting doesn’t come with an instruction book, but there are a lot of people who have made an effort at writing one… I still haven’t yet seen the Junior High Friend Instructions book, have you? All I want is to offer something I needed as a kid to someone who might need it now.

KLC: Now that you have many novels and awards under your belt, what words of publishing wisdom do you have for your fellow writers?

TSD: I still feel like a newbie, and in a way, I hope I always do. It reminds me to keep looking at what others are doing and learning from them. We all stand on the shoulders of the writers who came before us – so my wisdom, such as it is, is to read widely and deeply, across cultures and countries and time – and let your writing reflect a world as big and as honest as your heart can encompass.

KLC: What can Tanita S. Davis fans look forward to next?

TSD: Just this minute, I’m working on returning revisions for my next book which is Figure It Out, Henri Weldon, a book about a seventh grader working on relating to being mainstreamed in public school, and balancing a relationship with her older sister now that they’re sharing both a bedroom and a school, too. Full disclosure: I have three sisters. There’s a lot of bickering in the book that might sound familiar to people with siblings. This is a book about how sometimes you love people but they may not be who you choose to hang out with – but you can show up for each other anyway.

Thanks so much for inviting me to chat. Good writing to you!

For more inspiration, check out our interviews with Rita Williams-Garcia and Janae Marks.

Kristi Wright (co-editor) writes picture books and middle grade novels. Her goal as a writer is to give children a sense of wonder, a hopefulness about humanity, and a belief in their future. She is represented by Kurestin Armada at Root Literary. She is an active volunteer for SCBWI and a 12 X 12 member. Find her at www.kristiwrightauthor.com and on Twitter @KristiWrite.

COMMENTs:

0