hello!

JOIN US IN EXPLORING OTHERS' CRAFT AND BUILDING OUR OWN

I needed to put on my brave girl wings and write what felt right and natural to me, even though I was worried my agent and editor (and readers) might think it was weird. . . . I have always felt a deep, almost spiritual/magical connection with the natural world. I think a lot of people who spend time in nature feel it. That’s what was coming through in my writing.

interview by Erin Nuttall The thing I love most about Martha Brockenbrough’s writing is that she is unafraid. Yes, she’s imaginative, funny, thoughtful, and precise which all make her stories a joy to read, but to write bravely is a skill that few have and put Martha’s work on another plane. She slides easily between […]

Linda Urban’s stories are studded with angst, anguish, and hope, as well as problems, pathos, and humor. She is stellar at structuring stories so that something small, seemingly insignificant, becomes the integral to the climax and the protagonist’s understanding of the situation. In Talk Santa To Me, surprisingly, it’s a gaudy silver Christmas wreath that takes this hefty role.

From the All is Lost moment, right before Act 3 starts, to the Climax, The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy has followed each beat from Save the Cat, drawing readers in and compelling them to turn the page. But even after a stellar climax, the story isn’t done. There’s the opportunity to make the ending fully satisfying. Here’s how Ursu does it.

The book I’m working on needs an ending. I know it, and I don’t know what to do about it, because I don’t know how to write one. So I decided to see how Anne Ursu did it in her masterful The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy. In this series of blog posts, I’ll share what I’ve learned with you.

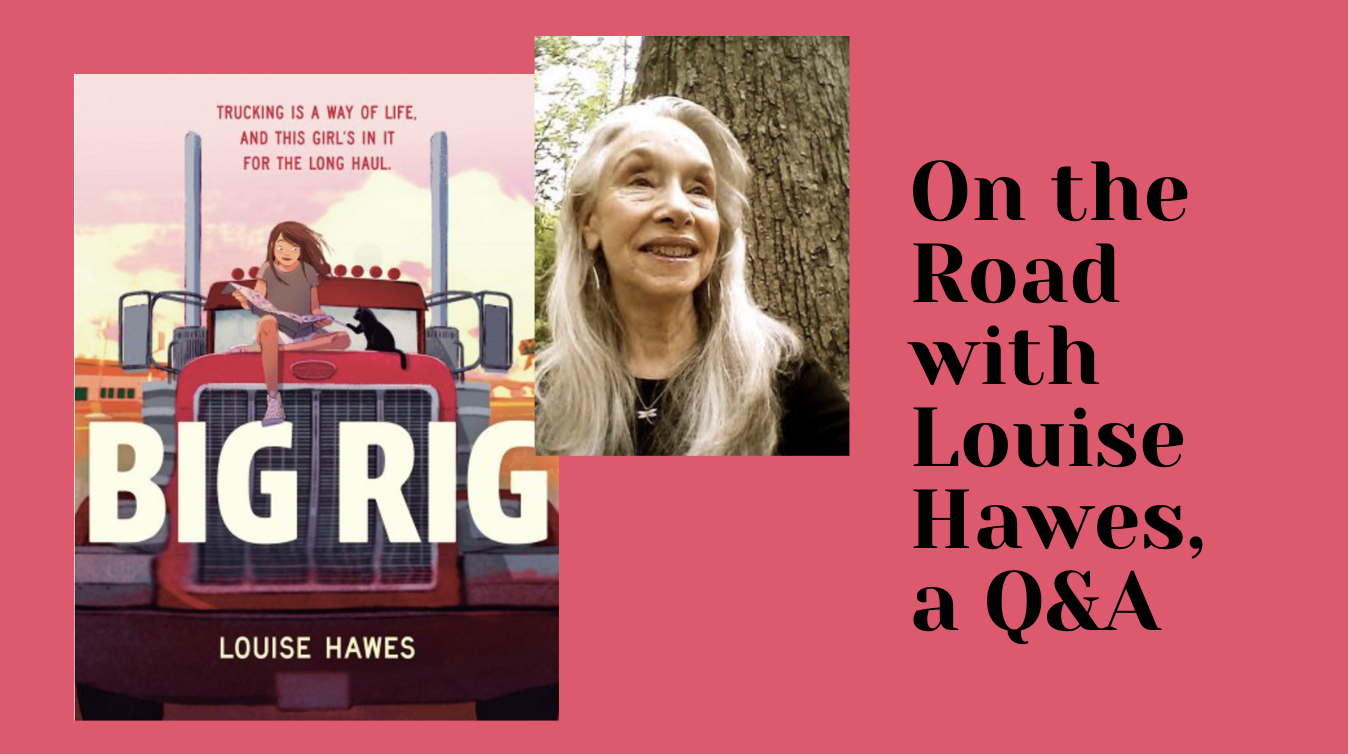

Louise Hawes: I often spend months (sometimes years) filling a notebook with my character’s responses and thoughts before I begin writing an actual draft. That notebook is all in long-hand, as you know, and I don’t stop to edit or erase anything. My characters’ letters are in the first person, and result from a fluid, bodily connection from my heart to my hand to the page. In contrast, my draft will be typed on a laptop, the far less spontaneous product of me thinking and feeling my way into a story that features the character whose voice has already filled my notebook.

By setting up a compelling story question in the reader’s mind, and then increasing the stakes throughout the second act, Joanna Ho has crafted the perfect crisis with its excellent Irreconcilable Goods options.

Sometimes when writing, we know what our character wants, but it’s a struggle to turn the nebulous desires into something tangible, something attainable, something concrete. Here’s how.

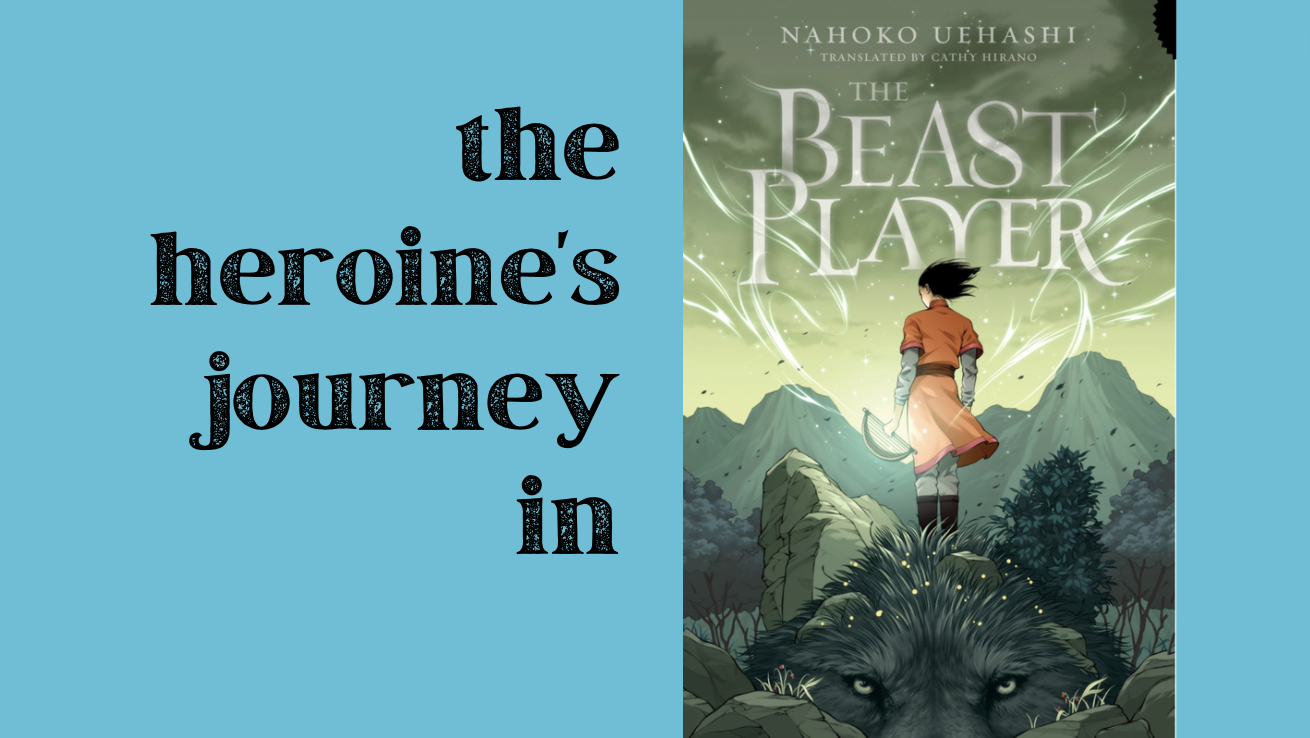

The Heroine’s Journey celebrates the gifts of the matriarch. It explores themes of family, community, collaboration, cooperation, and love. As an author, and as a person, it’s important to me to write books that support those values, so everyone who reads them can be inspired to evolve toward a more feminine, collaborative, resilient society. To illustrate the points I make in this post, I’ll be examining the Heroine’s Journey of Elin in The Beast Player, a Japanese YA fantasy by Nahoko Uehashi. Elin’s story is an excellent example of the Heroine’s Journey.

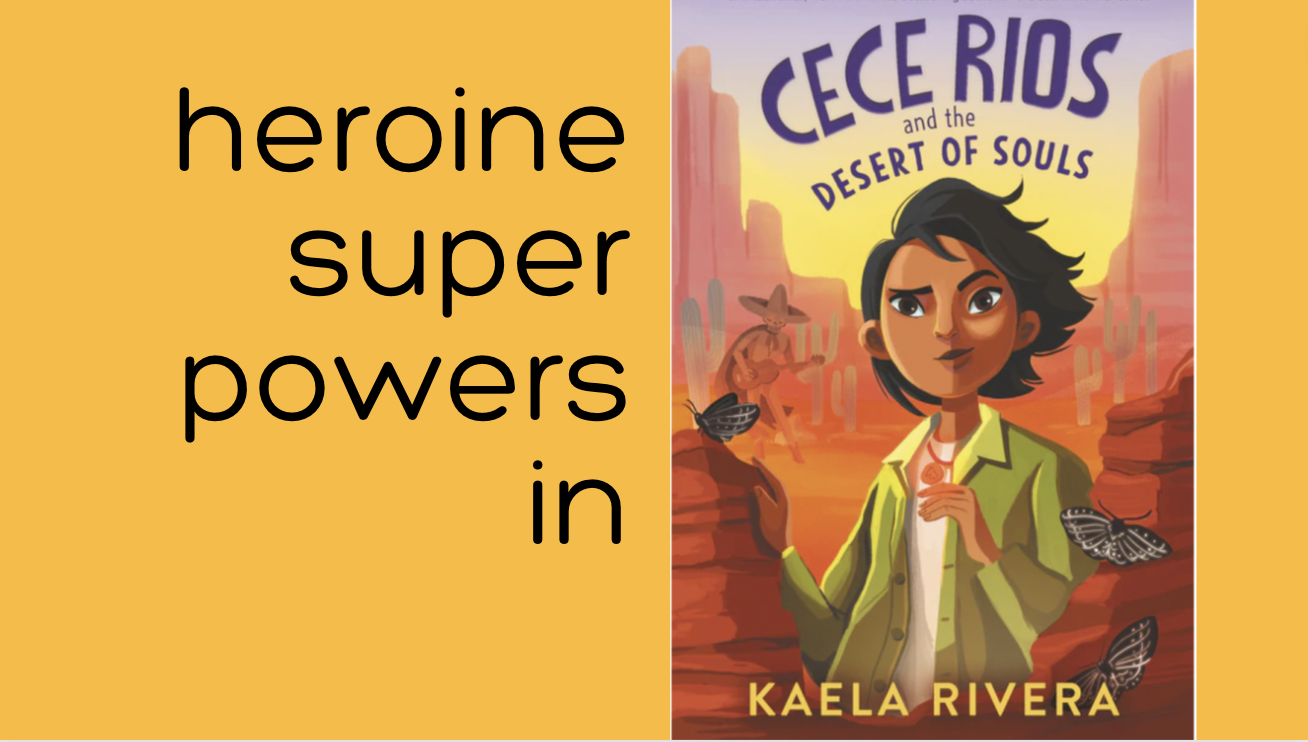

In order to understand how a heroine grows into her superpowers, I followed the heroine’s journey closely in three movies: Elsa in Frozen, Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and Meg in A Wrinkle in Time. I identified a common pattern for a superheroine’s recognition of and acceptance of her superpowers. Then I applied what I learned to analyze CeCe Rios and the Desert of Souls, a middle grade novel by Kaela Rivera to translate what I found in films to what might work in a novel.